words and music by Alan Sanderson

I hitched up my team and rode back east

In an early snowstorm in October

I left my wife and kids behind

But they were always on my mind

I wouldn’t be back home until DecemberOh, Rebecca, I’m so glad you’re safe at home

Heaven help me to find my wayI rode up the canyon through the snow

Falling deeper and deeper the further I go

Every mile would take its toll

And one of my horses wouldn’t pull

That stubborn thing was making me slowOh, Rebecca, I’m so glad our cellar’s full

That harvest will last a year

Oh, Rebecca, keep our table spread out full

God provide for you, my dearI came across the frozen refugees

Three hundred miles from their new home

Drifting snow, and too exhausted to pitch their tents

Out in the wilderness, aloneWeary fathers would give up sleep to guard their children

Starving husbands would give their last meal to their womenI heard the voices of the women and children crying

And saw the faces of the men who lay there dyingOh, Rebecca, keep that fire burning warm

I’ve never been so cold in all my life

Oh, Rebecca, hold our children in your arms

Lord, be with my angel wifeI filled my wagon with survivors

And several handcarts in tow

I could not believe

My horse now pulled like Hercules!

To the valley we goThank you, Lord, for these two hands

So I can serve my fellow manOh, Rebecca, while this storm is raging on

I’m so glad you’re safe at home

Oh, Rebecca, keep that fire burning warm

God protect you while I’m goneOh, Rebecca, I’m so glad you’re safe and warm

This awful wind is cold as sin

Oh, Rebecca, tell our kids I’m coming home

God be with you till we meet againAlan Sanderson: vocals, guitars, mandolin, banjo, bass

Notes

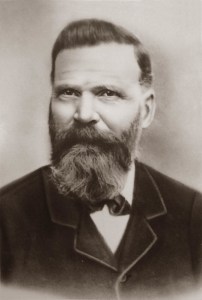

This song tells a true story taken from the autobiography of my third-great grandfather, Henry Weeks Sanderson (1829-1896), which also intersects with the life of my second-great grandfather on a different family line, John Rowley (1841-1893). Here is the story:

In 1856 John Rowley emigrated from England to the United States with his mother and siblings. After suffering religious persecution in their home country for over a decade they had decided to gather with other members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Utah Territory. They traveled by boat across the Atlantic and by rail across the eastern United States, and where the rail line ended in Florence, Nebraska they constructed handcarts and intended to walk the rest of the way. Unfortunately their company had bad luck in starting out too late in the season, being unable to purchase needed supplies along the way, losing a large number of their cattle in a stampede, and by the early onset of winter weather. They made it to central Wyoming and could go no further.

“John Rowley was 16, but he had been doing a man’s work day by day since leaving Iowa City. He pushed a handcart over 1,000 miles. Rowley family histories relate that at one crossing of the Sweetwater River, John helped carry children across the stream in the freezing water and helped women pull their handcarts across. By evening his wet clothes were frozen to his skin, and his mother had to warm him carefully to remove the frozen clothing.

“On another evening, he stood sentry duty in the freezing weather until all the stragglers came into camp. Exhausted, he lay down in the snow, and his hair froze to the ground. He lay there waiting to die. One of the company captains came along and gave him a painful kick. When he groaned, they realized he was still alive and placed him in the sick wagon, preserving his life” (from Rowley Family Histories: Treasures or Truth from the Lives of William and Ann Jewell Rowley and their Children 1835-1930, published by StoryWorks Publishers, 2004).

In early October 1856 Brigham Young learned about these struggling handcart companies. He said this in General Conference the next day:

“I will now give this people the subject and the text for the Elders who may speak. … It is this. On the 5th day of October, 1856, many of our brethren and sisters are on the plains with handcarts, and probably many are now seven hundred miles from this place, and they must be brought here, we must send assistance to them. The text will be, ‘to get them here.’ …

“That is my religion; that is the dictation of the Holy Ghost that I possess. It is to save the people. …

“I shall call upon the Bishops this day. I shall not wait until tomorrow, nor until the next day, for 60 good mule teams and 12 or 15 wagons. I do not want to send oxen. I want good horses and mules. They are in this Territory, and we must have them. Also 12 tons of flour and 40 good teamsters, besides those that drive the teams. …

“I will tell you all that your faith, religion, and profession of religion, will never save one soul of you in the Celestial Kingdom of our God, unless you carry out just such principles as I am now teaching you. Go and bring in those people now on the plains” (from Handcarts to Zion, Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1960, pp. 120–21, quoted by Gordon B. Hinckley in the October 1991 General Conference).

Henry Weeks Sanderson responded to this call. He was 26 years old when he left, and his wife Rebecca Ann Sanders (1832-1907) had just given birth to their fourth child. His autobiography includes these two paragraphs about the experience:

“At this time I had two yoke of oxen but before trading my horses, I had gone back on the road to help the hand cart company, the one that was so belated and suffered much. One of my horses generally objected to doing much pulling. When I met the company, the loads from several handcarts were loaded into my wagon, filling it to the top of the box. The carts were lashed to the rear axle of the wagon.

“Then as many persons as could sit comfortably got into the load, leaving no place for me except on the edge of the front end gate which I never used except in crossing streams. People were surprised at the way my team would pull. I was somewhat surprised myself. Another thing that surprised me was to find that the women had endured the hardships better than the men. When we arrived at Fort Bridger, teams met us from Salt Lake and I returned home” (from Henry Weeks Sanderson: from Blanford, Massachusetts to Fairview, Utah (an autobiography)).

Henry’s observation that many of the women had survived the hardships better than the men is consistent with other first-person accounts of the handcart companies:

“Flour was rationed to 6 oz. per day per person and there wasn’t much to go with it. Many were weakening from the lack of nourishing food. The young and the old and the weak began to die quitely [quietly]. Even the strong men who were secretely giving their portion to their fanlies [families] pulling their carts til they died. Soon rat[i]ons were cut again” (from Transcript for Dixon, Loleta Wiscombe).

The idea for this song came to me in 2021 when I reread Henry Sanderson’s autobiography and found the story about his stubborn horse interesting. The introduction to his autobiography explains why he included little stories like this:

“In writing a biography of my life, I will assure the reader that ostentation or pride had no place in my feelings. But I often think how gratifying it would be to me, had I a history of my forefathers. What a pleasure it would afford me.

“Although there might not be anything particularly notable, still it would be gratifying to my feelings and thinking that my posterity may have similar feelings.

“I have concluded after somewhat lengthy consideration to write a history of my life, also all that I know of my ancestry which may at some future time be printed in sufficient numbers of volumes to answer the needs of my children.

“And as it is designed for them only, not for the public, I hope that small details, or what might be termed frivolous matters, may prove of interest to posterity.”

Yes, Grandfather, we are grateful to have your life story in your own words, written by your own pen, and including so many details. I feel like I know you from reading your words. Thank you for sending them down through the generations of your family.

Henry Weeks Sanderson was a good man who was willing to help and serve whenever and wherever he was called upon to serve. His life was consecrated to the Lord. I hope that this song is consistent with his character, and that it will be enjoyed by his descendants and other interested people.

The composition of the song was influenced by the classic country/western ballads recorded by Marty Robbins in the 50’s and 60’s, which I found on CD at a thrift store some years ago and have greatly enjoyed. This was my first attempt at writing music in the genre, and I think it went reasonably well. I was also influenced by a Mark Knopfler ballad set in a similar time period called Prairie Wedding, which is a beautiful and haunting song. Special thanks to Tom for his feedback and suggestions during the mixing and mastering phase of the project. Also thanks to Marty Warburton for showing me a few licks on the banjo.

Finally, this song has caused me a lot of introspection about how its lessons can be applied to my life today. I could probably write another 1,000 words about this alone, but for the sake of brevity let me just include a list of questions I have pondered:

- What hardships or setbacks might we face in our efforts to gather with the Lord’s people?

- What amount of sacrifice is worth that reward?

- What has our prophet asked us to do to help rescue those who are in danger today?

- What miracles have you seen or experienced in today’s rescue efforts?

- Henry’s work to save and protect others began with his own family. How can we prioritize our family in our rescue efforts today?

- What stories and lessons from your life would you like to pass on to your descendants?

- What does this story teach us about service missionaries?

Info and Stats

- Production Dates: June 2021 — July 2023

- Equipment:

- Interface: Behringer Xenyx 1204USB, Behringer Ultra-DI DI400P

- Instruments: Takamine G-330 guitar, Saga Kentucky Mandolin 620, Royce nylon string guitar, Oscar Schmidt banjo, Chromaharp, Ibanez ASB140 bass

- Microphones: DIY condenser by Michael Willis

- Software:

- Linux Mint 20.2

- Ardour 7.3.0

- Dragonfly Hall Reverb

- x42-plugins: parametric equalizer, dynamic compressor, digital peak limiter

- Calf Studio Gear: multi-spread

- Total Tracks: 24

- Vocal: 16

- Instruments: 8

Alan – !I truly enjoyed your song, and the accompanying data which inspired your efforts. Thank you so much for sharing it. There were very good ideas outlined by your 4X grandfather. Times and values have seemed to negatively change over the years, unfortunately.

Hope all in your family are well !

CArol Woodman

LikeLike

Thanks, Carol! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Beautiful!

LikeLiked by 1 person